by Eugene Canales, CEO, Ferrari Tractor CIE

As an importer and dealer for small scale farm machines, I get questions about the availability of equipment for harvesting and threshing grains on a small scale. The stated objectives are to produce a staple food, a whole food grown organically or bio dynamically. Sometimes the inquirer wants to utilize grains or varieties not readily found in markets. In many cases, the foal is to add value, to change a readily found market into an end product to get a better return on work done. For others, it is to integrate farming and live stock production reducing the need to purchase supplemental feeds that may be overly expensive or more importantly contain doubtful ingredients. The growing interest in pastured poultry creates the need for reliable, organic and economical feed sources.

In deed, few important food crops require such low tech implements if you are willing to expend human energy in place of machines. The world over grains and other seed crops are routinely harvested with a hand held sickle or scythe and threshed by beating a bundle of stems over the side of a log and cleaned by tossing the grain into the air on a breezy day so that clean grain falls in a pile and chaff blows away - wheat or barley, rice, milo or millet the process is much the same. Variations may include using flails (jointed clubs) to beat stalks or driving oxen or equines over stalks laid on a paved surface to loosen the grain.

Today's grain grower generally wants to substitute at least some machine power for the manual labor and general messiness of the older way - to look at the options I have divided the operations into three tasks - cutting, gathering and threshing. In order to reduce the loss of crop by shattering, the seed plant is cut before it is dead ripe and allowed to ripen in a bundle or windrow on even on a paper tray. The idea is to reduce the chance of losing seeds during the cutting and windrowing process.

A sickle bar usually a double acting sickle bar cuts stems near ground. In the case of bean, one wants no lateral movement and the cut material is allowed to dry right where it had been growing. With wheat or barley some grain stems are moved laterally as they are cut to form a more concentrated windrow for drying. When a reaper binder is used the still upright grain stems are gathered at the instant they are cut and bundled and tied by a mechanism much like the knotter on a hay baler. The bundles are allowed to finish ripening in the field. The shocks seen in old pictures of grain fields are groups of bundles leaning against each other with the grain heads up like a flower bouquet.

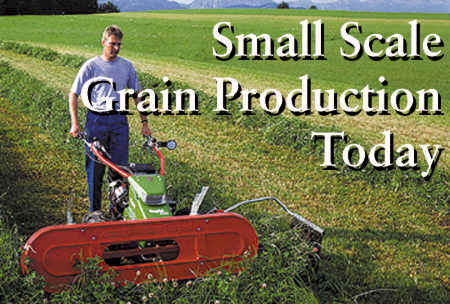

The picture at the top shows a Swiss made sickle bar mower equipped with a belt rake to cut and windrow in one pass. It is shown cutting hay but could just as readily be cutting wheat. Picture #2 shows an Italian self propelled reaper binder that can be walked behind or driven from a sulky seat. The binder device can also be removed so that machine can be used for hay making. An interesting thing about Italian agriculture is that so many farms are diversified with some vineyard, some orchard, some vegetable, some grain, etc. A farm whose cash income comes from grapes, for example, often grows 5 acres of wheat to make its own bread and pasta and where its climate permits some olive trees to have its own oil, but I digress. Picture #3 shows a reaper binder made by Mitsubishi of Japan. It cuts and bundles rice, wheat, barley etc that were planted in rows. Picture #4 shows a tractor with a three point mounted reaper binder, this one also Italian made, cuts 56" wide swath. It swings back 90 degrees for transport and to pass through gates. The PTO requirement is only about 20 HP and costs $9,500.

Now your crop is ripe in the field and ready to be threshed. If you have used a reaper binder, you have two choices. You can use a wagon to collect bundles to take them to the thresher or you can bring the thresher to the field. The small portable units are designed to take off the grain heads without handling all the straw. So you stick bundles with grain heads first into the thresher, then discard the decapitated stalks, thus machine need not chew up all the straw and deal with it in separating and cleaning the grain. This simplifies the machine and produces a cleaner product. By bringing bundle to the thresher at home you can opt for a running thresher with an electric motor, can easily put clean grain into storage tank and have the straw handy to livestock housing.

Picture #5 shows a simple treadle powered threshing drum made in India. The operator stands behind machine, lays a bundle of grain over rail so grain heads are stripped off by wire loops on rotating drum, The treadle cranks a gear box to rotate drum at around 450 rpm for wheat and half that speed for beams. The grain and hulls fall on a tarp spread in front of the machine and must then be windrowed by hand or with a fanning mill. Many variations of this machine are found all over the world. Some years ago the Rodale publishing company put out a book of plans for farmstead projects and had a set of plans for building one of these out of plywood.

Picture #6 shows an Italian thresher being used to process wheat. It has a clean out door that opens to expose entire separation chamber on opposite side of machine. A Plexiglas window lets you monitor separation process easily, differences in air pressure within chamber removes chaff. Output is 1200 lbs of clean wheat per hour. It's cost, about $12,500. Picture #7 shows a U.S. made stationary thresher designed for seed research work. It puts out a little over 100 lbs per hour. Interchangeable types of threshing drums and rasp bars allows it to handle many different seeds. The U.S. market is limited and most small machines go to deed companies and colleges and hence small production runs keep prices relatively high at about $5,000.

Crops that were cut and left loose in the windrow are generally pitch forked into a thresher pulled along the windrow for this task a slightly higher capacity trailer model like the one in picture #8 from Italy will do 1.5 tons per hour in wheat (about 1 acre) and costs $26,000. About 20Hp at PTO. It's self feeding intake table accepts loose material and maximizes production levels. Picture #9 shows a smaller U.S. 8Hp model with about 1000 lbs capacity with a narrow pick-up reel like on a hay baler or standard header.

Small standard self propelled and pull type combines went out of U.S. manufacture in the early 1960's - with new combine sales less that "1800" units in the US in the first quarter of 1999, you can see there is no prospect of a revival of small combines manufacture. With sales split between (6) manufactures there can be no mass production and prices will continue to rise well above the $125,ooo range. Indeed a local company here in Northern California produces rice research models with 7' headers for $110,000 each.

You might still find a few of these small old combines in working condition, but its becoming more and more difficult as these become collectors items. In California at any rate, you compete with seed research companies and antique farm machinery dealers. A small grain growing co-op in New Mexico tell of finding a working International Harvester 101 (1957) combine in Nebraska in 1997 and that it cost more to have it hauled to New Mexico that it cost to buy it from it's owner.

A small Allis Chambers model 60 "All Crop" is a real find if you can get one in working condition. These are pull types with their own engines and originally an operator sat in board to sew the grain sacks when they were full. Later many had bulk tanks instead. However, even these are not easy to transport any distance on a public road, without specialized equipment.

The current generation of small combines in the world today belong to two categories. The first are those being made for harvesting small holdings and sometimes in harsh conditions in the third world. Small walk behind combines are made in Japan and Korea and no doubt in other countries of Asia. The ones I have seen are the :CeCoCo" walk behind from Japan and the riding version from "Kubota" also from Japan. They were designed to harvest rice, wheat or barley grown in rows. The header looks like a corn header accepting two individual rows of grains at one time, threshing it and putting clean grain into cloth bags. For unknown reasons, Kubota refused to sell or permit the importation of anymore of these little combines.

Picture #10 shows a Mitsubishi four row combine that was recently imported to California. It is equipped with crawler tracks for work in soft, wet ground. Note grain tank swings out so it can dispense into sacks. It can unload with the over head auger as well. It costs about $55,000 delivered.

The combine in picture #11 is a "Cicoria" from Italy. It has a 6'6" general crop header and is powered by a 38Hp diesel engine. It's 92" wide, 16' long and weighs 5,390 lbs. and has a hydrostatic transmission. this small combine is sold to southern Europe, north Africa and the middle east where growing conditions are often difficult and crop yields are often low. It incorporates a quite modern axial threshing drum arrangement. The longer threshing drum of this system gives longer contact time for crop material between threshing drum and the greater surface area of the concave. This provides better grain separation and less need to recycle unthreshed heads. This cutaway in picture #12 is of this same companies stationary thresher that uses the same principle.

The second group of small combines are the research types. They are generally patterned after the large commercial combines just scaled down to fit small research plots. The emphasis in their design is to make it easy and fast to clean out the entire system between plots. The job is to keep samples distinct between the replicated plots that are often under one hundred square feet each. The best example of this type of machine is the Austrian Winterstieger. In picture #13 it is shown equipped with a standard grain header 5 feet wide. Several types of special headers permit it to process an unusually wide assortment of crops from small grains including rice to beans to sunflowers and corn. It is designed to allow very rapid changes of concaves, shakers and sieves. It is 76" wide, 19' long and weighs about 4400 lbs. Price is $70,000 (with one header).

An interesting example of the old becoming new is the stripper headers recently introduced to combines. Instead of cutting the grain stems to pull grain head into combine, the stripper header combs the grain off the stem leaving the stalk standing. In rice fields this type of combine works twice as fast as the conventional header type. That's because almost no straw has to go through threshing drum, or has to be separated out during cleaning phase. What makes this remarkable is that one of the earliest devices invented to mechanize grain harvesting during the middle ages was a wagon pushed by oxen that had a serrated horizontal cutting bar with vaguely arrowhead shaped teeth set side by side. As this was pushed into growing crop, grain stems slid into the notches between the teeth and heads cut/pulled off and fell backwards into the wagon. The modern version uses very similar shaped "teeth" but they are set on several bars on a rotating header drum. the rotation tends to sweep grain into stripper reducing grain loses that the original version, built in the middle ages, no doubt experienced. The lesson, be patient it sometimes takes 7 or 8 hundred years to get it right.

It may seem odd to count balers as possible machine choices where grains are the interest, but for those interested primarily in raising quality feeds for use at home, it makes sense many kinds of livestock will thresh their own grains and other seed crops and benefit in the doing. Poultry do not need everything pre-threshed although young birds do need broken grains to start them. Some of the stalks, leaves, and other trash become feed as well as litter to soak up urine and manure for later composting. Sheep and goats are quite effective at milling their own grains and need the high roughage content to keep their digestive tracts functioning well. Watch a pig on pasture and you will see they browse almost like goats and turn them loose in an oak groove and see how they deal with acorns.

Picture #14 depicts a small round baler that makes an 18" x 30" round bale that is wrapped in netting. This netting permits it to bale crumbly and short material that would be lost in a standard baler. What's remarkable is that this little baler is powered by a 12 Hp walking tractor. The baler in picture #15 is a similar type but this time powered by PTO of small four wheel tractor and also wraps bale in netting. In the last picture #16, there is a small square baler that only requires a 20 Hp tractor to power it, that is ideal for small fields.

On the whole, it seems to me the smaller portable thresher that can be moved around on a pick up truck or in a trailer is going to be the best choice. In my opinion, it will become more and more critical that seed crops be grown in ever more remote and non-traditional locations and rotated frequently to preserve variety integrity from the encroachment of genetically engineered crops with their potential for establishing niche markets for the very old grains of the Americas. Quinoa and Amaranth await the skill and determination of entrepreneurs, like the Lundbergs of brown rice fame and the people who made Granola a familiar name. Perhaps these little known grains will first reach the larger market as mixtures with better known grains much like wild rice is often first experienced as rice pilaf. In any event, it all starts small scale.

And if you produce high quality foods but fail to reach the pinnacle of marketing success, and are defeated in the establishing regional or national brand, what then? Well, you will have worked and learned, enjoyed the taste and nutritional benefits of a very basis food, shared the staff of life with your family and circle, and fed your livestock well and some strangers too. You will have added a degree or two of security to the worlds food chain. So much for the "agony of defeat".

This article appeared in a different form in the September, 1999 issue of ACRES USA, the voice of Eco-Agriculture

For more information: Contact Eugene Canales / Ferrari Tractors via phone at 1-530-846-6401, Fax 1-530-846-0380 P.O. Box 1045, Gridley, California 95948